Although I blog frequently about Bulgaria and Romania

(between which countries I have been dividing my life in these last 5 years), I

should say more about the other countries in which I have spent significant

time – Uzbekistan, Azerbaijan and Kyrgzstan, for example. A New York Review of

Books blogpost and a review in The Nation of

a forgotten Azeri satirical magazine of a century ago gives me an opportunity to rectify this oversight. To give an easy introduction

to the various actors, I borrow from the review in the Nation - adding in,

where appropriate, links one of which is to a recent book on the

magazine containing many of the caricatures with powerful line drawing and

colours.

The backstreets of Baku, the capital of Azerbaijan, have a

certain, winding magic. They house former caravanserai, once flophouses offered

to travellers throughout central Asia, that have today been polished up into

candlelit restaurants. Tall, grey blocks mingle with flourishes of Persian

architecture - a symbol of Baku's straddling geography between Russia and Iran.

But there are dozens of bookshops tucked away in these streets, shelves stacked

with first editions and Soviet periodicals from the city's communist era, which

ended in 1991.

It was in one of these booksellers near Maiden Tower that

Slavs and Tatars, a collective of artists and writers, discovered a true bibliophile's dream:

editions of one of the region's most daring yet overlooked satirical

publications - Molla Nasreddin.

Stating their sphere of interest as everything east of the former Berlin Wall

and west of the Great Wall of China, Slavs and Tatars make this loosely defined

area of Eurasia their patch. Starting as a reading group that shared

translations of books from this region (what they call "an arcane version

of the Oprah Winfrey book club"), they've since exhibited sculptures and

installation work in museums internationally, and been part of group shows at

The Third Line gallery in Dubai.

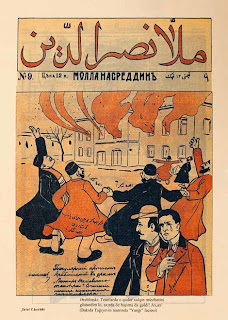

"The illustrations drew us to Molla Nasreddin,"

says Slavs and Tatars. "They're reminiscent of Honore Daumier or Toulouse

Lautrec." Molla Nasreddin was founded in 1906 by editor-in-chief Jalil

Mammadguluzadeh and satirist-poet Mirza Sabir, both proud Azeris yet champions

of a "modern" and markedly western system of values. It espoused this

worldview via beautifully wrought yet withering cartoons and editorials that

remain biting today.

Few were spared the editorial wrath: suffocating and

outmoded fanatics, meddling European and Russian imperial powers, the position

of women in society at that time and the hypocritical elite. Education,

equality and regional independence, through a lens of secularism, was Mammadguluzadeh

and Sabir's vision for central Asia's future. It was penned in Azeri Turkish in

three different scripts - Arabic, Cyrillic and Latin alphabets - showing the

three forms that the language went through as Azerbaijan passed into Soviet

hands. This made translation into English difficult when Slavs and Tatars set

out to publish a reader in 2011, titled "Molla Nasreddin: The Magazine That

Would've, Could've, Should've". Here's another good review which gives a sense of the treasures the book holds

The book features their selections from 3,000 illustrations,

curated into the different avenues of critique that the magazine took - such as

Education, Colonialism and Women.

One illustration, for instance, shows two Azeri women

wrapped from head to toe in fabric, and pointing in envy at the barred windows

of a prison. The caption alongside reads: "Sister, look how lucky they

are: they have windows!"

In another, five beaten-down Azeri men carry bespectacled

donkeys on their back; plumes of smoke rise from long cigarette holders in the

mouths of these remarkably aristocratic looking beasts.

Despite moving offices to and from Georgia and Iran,

intermittent bans, and 10 years of the Soviets increasingly shoving editorial

directives down the throats of the magazine's staff, Molla Nasreddin survived

until 1931. Simultaneously, a cloud of obscurity seemed to settle over a region

that, says Slavs and Tatars, had been one of the most intellectually and

politically important places in the past 2,000 years.

"If anybody even takes notice of this region, they

think of it as obscure, especially the more west you go - you talk to people

about Kyrgyzstan, and you might as well be talking about Star Wars," says

Slavs and Tatars. "But Baku was producing half of the world's oil until

the first half of the 20th century," noting as well that Azerbaijan was

one of the first countries in which women could vote (well before the UK), and

publications such as Molla Nasreddin demonstrate an intellectual, progressive

rigour from this part of the world that has been so far overlooked.

"That's why we're called Slavs and Tatars and not by

our real names: it's not the work of a group of artists but the work of a

region that has many nationalities, and had a shared heritage at some point.

"From the point of view of the West, with this nonsense that passes as

conventional wisdom that the West and Islam are on a collision course; you have

to look at a part of the world where they have long coexisted." Namely,

Eurasia.

The collective say, however, that Molla Nasreddin is also

their antithesis in that it took modernity to mean westernisation. "We

don't believe that at all, in fact we believe in quite the opposite - more of

an indigenous or hybridised form of modernity." But they still acknowledge its historical

significance: "It's a shame that it came down to us as artists and writers

in the early 21st century to rediscover one of the most important publications

of the Muslim world," they continue. "That's testament to how

overlooked this part of the world is.

"Very few people would spend two years of their life

working on something they disagree with, but we are living in an increasingly

insular world intellectually - less and less are we embracing the things that

we disagree with."

I’ve been wanting for some time to do a post (if not a

booklet!) about beautiful publications - which bring together layout; font;

illustrations; paper quality; binding; and writing. It's a challenging

combination which some cookery books almost manage (with the exception of font

and writing)

.jpg)