Christmas may still be 2 months away but one reputable blog has come with the sort of quiz we play at that time of the year - asking people “which book provides support, or is a book to which one often returns. And the answer cannot be the Bible”. As the participants in the subsequent discussion thread recognise, it’s not an easy question to answer. Most of our reading is novels and specialist stuff. There are, of course, classic novels (both old and new) to which we can and do return but several of the discussants say that it is poetry to which they go back – I would tend to agree. I often turn to TS Eliot, Bert Brecht, WS Graham and Norman MacCaig (sadly BBc doesn't allow me access this last), for example. What about my readers?

My subject today is training of public officials in ex-communist countries.

The European Union has spent many hundreds – if not thousands - of millions of euros on training of public servants in the accession states; in Eastern Europe and central Asia (and continues to do so in the Operational Programmes of its Structural Funds with which I am currently involved here in Bulgaria). Despite the European Commission emphasis on evaluation, I am not aware of any critical evaluation it has commissioned of that spending – nor of any guidelines it has issued to try to encourage good practice in this field of training public officials (It has issued, in recent years, guidelines on “good governance”, internal project monitoring, project cycle management, institutional assessment and capacity development, ex-ante evaluation). And, in particular, there is nothing available for those in transition countries who want to go beyond the task of managing one specific programme of training and actually build a system of training which has the key features of –

• Continuity

• Commitment to learning and improvement

A transition country is lucky if its officials and state bodies actually benefit from a training programme – with training needs being properly assessed; relevant and inspiring courses constructed; and delivered (by skilled trainers) in workshops which engage its participants and encourage them to do things differently in their workplace. Too often, many of these ingredients are missing. But, even if they are present, the programme is usually an ad-hoc one which fails to assist the wider system. The trainers disappear – often to the private sector; their training materials with them. No improvement takes place in the wider system of training public officials.

For 20 years now I have led public administration reform projects in a variety of “transition” countries in central Europe and central Asia – in which training and training the trainer activities have always been important elements. Initially I did what most western consultants tend to do – shared our “good practice” from western europe. But slowly – and mainly because I was no longer living in western Europe – I began to see how little impact all of this work was having. I summarised my assessment recently in the following way-

• Most workshops are held without sufficient preparation or follow-up. Workshops without these features are not worth holding.

• Training is too ad-hoc – and not properly related to the performance of the individual (through the development of core competences) or of the organisation

• Training, indeed, is often a cop-out – reflecting a failure to think properly about organisational failings and needs. Training should never stand alone – but always be part of a coherent package of development – whether individual or organisational.

• It is critical that any training intervention is based on “learning outcomes” developed in a proper dialogue between the 4 separate groups involved in any training system – the organisational leader, the training supplier, the trainer and the trainee. Too often it is the training supplier who sets the agenda.

• Too many programmes operate on the supply side – by running training of trainer courses, developing manuals and running courses. Standards will rise and training make a contribution to administrative capacity only if there is a stronger demand for more relevant training which makes a measurable impact on individual and organisational performance.

• In the first instance, this will require Human Resource Directors to be more demanding of training managers – to insist on better designed courses and materials; on proper evaluation of courses and trainers; and on the use of better trainers. More realistic guidelines and manuals need to be available for them

• Workshops should not really be used if the purpose is simply knowledge transfer. The very term “workshop” indicates that exercises should be used to ensure that the participant is challenged in his/her thinking. This helps deepen self-awareness and is generally the approach used to develop managerial skills and to create champions of change.

• Workshops have costs – both direct (trainers and materials) and indirect (staff time). There are a range of other learning tools available to help staff understand new legal obligations.

• HR Directors need to help ensure that senior management of state bodies looks properly at the impact of new legislation on systems, procedures, tasks and skills. Too many people seem to think that better implementation and compliance will be achieved simply by telling local officials what that new legislation says.

• A subject specialist is not a trainer. Too few of the people who deliver courses actually think about what the people in front of them actually already know.

• The training materials, standards and systems developed by previous projects are hard to find. Those trained as trainers – and companies bidding for projects – treat them, understandably as precious assets in the competitive environment in which they operate and are not keen to share them!

And this last point perhaps identifies one of the reasons why transition countries have found it so difficult to establish public training systems to match those in the older member states. From the beginning they were encouraged to base their systems on the competitive principle which older member states were beginning to adopt. Note the verb - "were beginning". And, of course, there is no greater zealot than a recent convert. So experts who had themselves learned and worked in systems subsidised by the state appeared in the east to preach the new magic of competition. And states with little money for even basic services were only too pleased to buy into that principle. The result is a black hole into which EU money has disappeared.

I will, in the next post, try to set out some principles for capacity development of public training systems in transition countries.

The photograph is of me at the communal table of Rozinski Monastery here in Bulgaria - taken a couple of year ago by my friend and colleague Daryoush Farsimadan, I think there is something appropriate there....

a celebration of intellectual trespassing by a retired "social scientist" as he tries to make sense of the world..... Gillian Tett puts it rather nicely in her 2021 book “Anthro-Vision” - “We need lateral vision. That is what anthropology can impart: anthro-vision”.

what you get here

This is not a blog which opines on current events. It rather uses incidents, books (old and new), links and papers to muse about our social endeavours.

So old posts are as good as new! And lots of useful links!

The Bucegi mountains - the range I see from the front balcony of my mountain house - are almost 120 kms from Bucharest and cannot normally be seen from the capital but some extraordinary weather conditions allowed this pic to be taken from the top of the Intercontinental Hotel in late Feb 2020

Friday, October 28, 2011

Thursday, October 27, 2011

Downside of Sofia Charms?

I’ve talked several times on the blog about the charm of central Sofia – with its parks and buskers with their retro music; narrow streets, small shops and atmosphere, the owners on the doorstep with a coffe and cigarette talking with friends. Of course the downside of such charm is that those who run the tiny vegetable, dressmakers, tricotage (thread) shops and various types of galleries barely make a living. How many of them are rented, I wonder, and therefore vulnerable to landlord rental hikes and commercial redevelopment? And I wonder how many of those who engage in this sort of soulless redevelopment realise what they are destroying. Is there nothing which can counter this Mammon? Do the city authorities realise what an asset they have? If so, are they doing anything about it? The lady mayor is certainly a huge improvement on her predecessor who, I was told yesterday, used to charge significant sums for those who wanted an audience with him to discuss their problems.

In the Yavorov District on Tuesday – a leafy and lively area near the University and just across from the great park which extends from the Eagle bridge and the football stadium for more than a kilometre east along the Express way which starts the run to the Thracian Valley, Plovdiv and Burgas. Looked at an elegant old flat which had housed the middle managers of the railways in the 30s in an area otherwise known as a residential one for the military at the beginning of the last century. And ventured into a small basement antique shop which was a real alladin’s cave of old Bulgarian and Russian stuff. The prize haul was a set of the small, shaped bottles in which rakia used to be drunk.

They seem to be 1950s or early 1960s – with wry humour stamped on to the glass. I haven’t discussed rakia yet in the blog (apart from the blog about the recent visit to Teteven). First time I tasted rakia in 2002, when I sped through the country on the way to the Turkish Aegean, I found it inspid. But I have now had a chance to taste various brands – and compare it with various Romanian palinka – and have become an afficiando. Here is a write up of one brand which won a few years back a silver medal in the International Review of Spirits Award -

In the Yavorov District on Tuesday – a leafy and lively area near the University and just across from the great park which extends from the Eagle bridge and the football stadium for more than a kilometre east along the Express way which starts the run to the Thracian Valley, Plovdiv and Burgas. Looked at an elegant old flat which had housed the middle managers of the railways in the 30s in an area otherwise known as a residential one for the military at the beginning of the last century. And ventured into a small basement antique shop which was a real alladin’s cave of old Bulgarian and Russian stuff. The prize haul was a set of the small, shaped bottles in which rakia used to be drunk.

They seem to be 1950s or early 1960s – with wry humour stamped on to the glass. I haven’t discussed rakia yet in the blog (apart from the blog about the recent visit to Teteven). First time I tasted rakia in 2002, when I sped through the country on the way to the Turkish Aegean, I found it inspid. But I have now had a chance to taste various brands – and compare it with various Romanian palinka – and have become an afficiando. Here is a write up of one brand which won a few years back a silver medal in the International Review of Spirits Award -

Golden salmon colour. Vanilla and toasted nut aromas. nice oily texture. Dryish, vanilla bean oily nut flavors. Finishes with a lightly sweet powdered sugar and pepper fade. A nice texture and finish but could use more on the mid-palateFinally – a great blogposts about traditional sheep farming by someone who spent a couple of months with the shepherds and cheese makers in the Carpathians.

Wednesday, October 26, 2011

The power of images

George Monbiot’s post in yesterday’s Guardian gave me some good links to papers trying to encourage a debate which is long overdue -

We think we know who the enemies are: banks, big business, lobbyists, the politicians who exist to appease them. But somehow the sector which stitches this system of hypercapitalism together gets overlooked. That seems strange when you consider how pervasive it is. It is everywhere, yet we see without seeing, without understanding the role that it plays in our lives. I am talking about the advertising industry. For obvious reasons, it is seldom confronted by either the newspapers or the broadcasters. The problem was laid out by Rory Sutherland when president of the Institute of Practitioners in Advertising. Marketing, he argued, is either ineffectual or it "raises enormous ethical questions every day". With admirable if disturbing candour he concluded that "I would rather be thought of as evil than useless." A new report by the Public Interest Research Centre and WWF opens up the discussion he appears to invite. Think of Me as Evil? asks the ethical questions that most of the media ignore – and adopts a rigorous approach, seeking out evidence. Our social identity is shaped, it argues, by values which psychologists label as either extrinsic or intrinsic. People with a strong set of intrinsic values place most weight on their relationships with family, friends and community. They have a sense of self-acceptance and a concern for other people and the environment. People with largely extrinsic values are driven by a desire for status, wealth and power over others. They tend to be image-conscious, to have a strong desire to conform to social norms and to possess less concern for other people or the planet. They are also more likely to suffer from anxiety and depression and to report low levels of satisfaction with their lives.A pamphlet from the Compass Think Tank also picks up the issues. Less measured in its tone than the PIRC publication, it argues that advances in psychology. neurology and technology have given advertising insidious new powers; points to the interventions which governments have been making since the 1960s in relation to tobacco, protection of children etc and makes a series of recommendations – including the banning of advertising in public spaces, a measure introduced recently with great success apparently in the mega-city of Sao Paulo (20 million population).

We are not born with our values: they are embedded and normalised by the messages we receive from our social environment. Most advertising appeals to and reinforces extrinsic values. It doesn't matter what the product is: by celebrating image, beauty, wealth, power and status, it helps create an environment that shifts our value system.

Advertising may, as Monbiot suggests, have succeeded in the past few years in keeping its head down but there was a time when it was under attack. In my youth, I remember the impact of Vance Packard’s The Hidden Persuaders (1956 or so) and, a few years later, Jk Galbraith’s powerful dissection (in his 1967 book The New Industrial State) of the reality of the market and the way large companies shaped demand. Of course, the downfall of large companies a couple of decades later by the more flexible Apple and Microsoft companies was widely used to discredit Galbraith’s thesis. A more measured assessment of his arguments about corporate power (and indeed contribution to economics) appeared in the Australian Review which said -

Two rejoinders are in order. First, the qualitative evolution of economic systems highlights that grand generalisations are necessarily period-specific. The character of the automobile market after the mid-1970s may be instructive, but it does not vitiate generalisations on its character before the mid-1970s.Most people, however, want to see the world’s economies refloated and jobs returning. Whatever their gripes about advertising, they see it as a means of aiding that objective. Those who see the huge waste and social destruction of our present system have an upward struggle. I was pleased to see people like Fritjof Capra and and Hazel Henderson taking the argument into the enemy camp with a pamphlet published in 2009 by the Institute of Chartered Accountants of England and Wales – entitled Qualitative Growth. I wouldn’t say it is the most convincing paper for such an audience – and am sorry that its references didn’t give wider sources eg Douthwaite.

Second, Galbraith’s generalisations regarding the unbridled power of the corporate sector retain direct relevance to other segments of the corporate sector—the military-industrial ‘complex’ (including constructors), big oil (centred on Exxon Mobil), the medical-insurance complex, big chemical, big tobacco, big retail (Wal-Mart) and big finance. It is curious that Galbraith’s critics have not sought to juxtapose Galbraith’s focus with current developments that involve corporate actors writing the legislation that governs their sector (medical-insurance), heading off legislation or penalties that adversely effect their sector (oil, chemical, tobacco, etc.), or channeling foreign policy with heinous implications (weapons contractors and constructors).

On the related issue of consumers as pawns, it is true that American consumers belatedly exercised autonomy in electing to buy the automobiles of foreign manufacturers (albeit a sub-sector of the market remains subservient to the US auto giants’ emphasis on sports utility vehicles and the preposterous Hummer). Galbraith rightly asked the rationale for the then vast sums spent by producers on marketing (a question never satisfactorily addressed by mainstream economists)

The problems of the economic system we have can be best be summed up in two words - dissatisfaction and waste. Advertising creates the first - and the economic machine wastes people, resources and the planet. And yet its ideologues have erected a propoganda machine which tells us that it is both efficient and effective! What incredible irony!

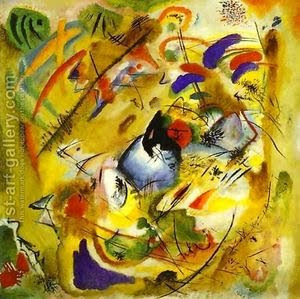

Last evening was spent very pleasantly at one of Astry Gallery’s great vernissajs, celebrating the opening of yet another exhibition. This time the work of Natasha Atanassova and Nikolay Tiholov. Natasha is on the left and Vihra, the gallery impressario, on the right. And the painting at the top of the post is one of two I bought - this one by Natasha. The second is by Nikolay and is here -Astry Gallery (under Vihra's tutelage) is unique for me amongst the Sofia galleries in encouraging contemporary Bulgarian painting. Two things are unique - first the frequency of the special exhibitions; but mainly that Vihra follows her passion (not fashion). I am not an art professional - but Vihra has a real art of creating an atmosphere in which people like me can explore. I have been to a couple of other exhibition openings here and they were, sadly, full of what I call "pseuds" - people who talked loudly (mostly Embassy people) and had little interest in the paintings (except perhaps their investment value). Vihra and her Astry Gallery attract real people who share her pasion and curiousity. It is always a joy to pop in there - and talk to her, visitors, artists, other collectors and her father.

Sunday, October 23, 2011

Is complexity theory useful?

Thirty years ago terms such as "policy failure” and "implementation drift” were all the rage in political science circles – with the implicit assumption that such drift was a bad thing ie that the original policy had been and/or remained relevant and effective. Nowadays we are more sceptical about the capacity of national (and EU) policy-making – and (therefore?) more open to systems thinking and complexity theory and its implications for public management. Certainly Gordon Brown’s fixation with targets was positively Stalinistic – and was progressively softened and finally abolished on his demise. I have blogged several times about the naivety of the belief that national governments (and, logically, companies) could control events by pulling levers – sometimes calling in aid posts from the thoughful blog Aid on the edge of chaos ; John Seddon and his systems approach and Jake Chapman who wrote a useful paper some time ago about the implications of systems thinking for government.

I have never, however found it easy to get my head around the subject. I am now reading the Institute of Government’s recent pamphlet on System Stewardship which is exploring the implications for english Civil Service skills of the Coalition government apparent hands-off approach to public services ie inviting a range of more localised organisations to take over their running – within some sort of strategic framework. The task of senior civil servants then becomes that of designing and learning from (rather than monitoring (?) the new system of procurements. My immediate thought is why so few people are talking about the reinvention of English local government (turned in the last 2 decades into little more than an arm of central government) – ie of inviting/requiring local authorities (rather than central government) to do the commissioning. The logic of complexity theory for collective organisations is presumably to reduce hierarchies and move decision-making as near as possible to individuals in their localities. Neoliberals say this means markets (dominated by large oligopolies); democrats say it means municipalities committed to delegation and/or mutual societies and social enterprises; and many northern Europeans would argue that they have the answer with their mixture of coalition governments, consultation and strong municipalities. But those who write in the English language don't pay much attention to that.

When I googled "stewardship”, I realised it has, in the last few years, become a new bit of jargon – and have to wonder if it is not a new smokescreen for neo-liberalism.

For the moment, I keep an open mind and will be reading three papers I have found as a result of this reading – a rather academic-looking Complexity theory and Public Administration – what’s new?; a rather opaque-looking Governance and complexity – emerging issues for governance theory; and a more useful-looking Governance, Complexity and Democratic participation – how citizens and public officials But I'm not holding my breath for great insights - just seems to be academic reinvention by new labels.

Saturday, October 22, 2011

In Memoriam; Ion Olteanu 1953-2010

I dedicate this post to the memory of Ion Olteanu – a Romanian friend who died a year ago and whose anniversary was today at the Scoala Centrala in Bucharest. Sadly, being in Sofia, I wasn’t able to attend. He was one of a tiny minority in post-Ceausescu Romania with a vision for Romania – and worked tirelessly and with great sacrifice and professional passion with its adolescents to try to realise it. He had a marvellous and unique combination of tough logic and tender care.

I hope he will consider it a suitable memorial comment.

In recent years, some of us consultants in admin reform have found ourselves drafting manuals on policy-making for government units of transition countries. I did it ten years ago for the Slovak Civil Service (it is one of the few papers I haven't yet posted on the website). I’m sorry to say that what is served up is generally pure fiction – suggesting a rationality in EC members which is actually non-existent. I like to think that I know a thing or two about policy-making. I was, after all, at the heart of policy-making in local and regional government at the height of its powers in Scotland until 1990; I also headed up a local government unit which preached the reform of its systems; and, in the mid 1980s I got one of the first Masters Degree in Policy Analysis. So I felt I understood both what the process should be – rational, detached and phased - and what in fact it was – political, partial and messy. I was duly impressed (and grateful) when the British Cabinet Office started to publish various papers on the process. First in 1999, Professional policy-making for the 21st Century and then, in 2001, a discussion paper - Better Policy Delivery and Design. This latter was actually a thoroughly realistic document which, as was hinted in the title, focused on the key question of why so many policies failed. It was the other (more technical parts) of the british government machine which showed continued attachment to the unrealistic ratonal (and sequentially staged) model of policy-making – as is evident in this response from the National Audit Office and in the Treasury model pushed by Gordon Brown.

The Institute of Government Think Tank has now blown the whistle on all this – with a report earlier in the year entitled Policy-Making in the Real World – evidence and analysis. The report looks at the attempts to improve policy making over the past fourteen years – and also throws in some excellent references to key bits of the academic literature. Based on interviews with 50 senior civil servants and 20 former ministers, along with studying 60 evaluations of government policy, it argues that these reforms all fell short because they did not take account of the crucial role of politics and ministers and, as such, failed to build ways of making policy that were resilient to the real pressures and incentives in the system.

The Institute followed up with a paper which looks at the future of policy making “in a world of decentralisation and more complex problems” which the UK faces with its new neo-liberal government The paper argues that policy makers need to see themselves less as sitting on top of a delivery chain, but as stewards of systems with multiple actors and decision makers – whose choices will determine how policy is realised. As it, with presumably unconscious irony states, “We are keen to open up a debate on what this means. There is also a third paper in the series which I haven’t had a chance to read yet.

In this year’s paper to the NISPAcee Conference, I raised the question of why the EC is so insistent on accession countries adopting tools (such as policy analysis; impact assessment; professional civil service etc) which patently are no longer attempted in its member states. Is it because it wants the accession countries to feel more deficient and guilty? Or because it wants an opportunity to test tools which no longer fit the cynical West? Or is it a cynical attempt to export redundant skills to a gullible east?

Friday, October 21, 2011

There is another way

I am grateful to a Balkans historian, an Irish economist and an anonymous Canadian for this post. Tom Gallagher pointed me to a post on the website of David McWilliams one of whose discussants gave the following info -

“Property,” Fr. José wrote, “is valued in so far as it serves as an efficient resource for building responsibility and efficiency in any vision of community life in a decentralized form.” José’s first step was the education of the people into the Distributist ideal. He became the counselor for the Church’s lay social and cultural arm, known as “Catholic Action,” and formed the Hezibide Elkartea, The League for Education and Culture, which established a training school for apprentices. He helped a group of these students become engineers, and later encouraged them to form a company of their own on cooperative lines. In 1955, when a nearby stove factory went bankrupt, the students raised $360,000 from the community to buy it. This first of the co-operatives was named Ulgor, which was an acronym from the names of the founders.

And the "way" which is shown in the picture is the new road which the village has built at the bottom of my garden. Not as fearsome as I had feared!!

Recently, the workers in the Fagor Appliance Factory in Mondragón, Spain, received an 8% cut in pay. This is not unusual in such hard economic times. What is unusual is that the workers voted themselves this pay cut. They could do this because the workers are also the owners of the firm. Fagor is part of the Mondragón Cooperative Corporation, a collection of cooperatives in Spain founded over 50 years ago.The story of this remarkable company begins with a rather remarkable man, Fr. José Maria Arizmendiarrieta, who was assigned in 1941 to the village of Mondragón in the Basque region of Spain. The Basque region had been devastated by the Spanish Civil War (1936-1938); they had supported the losing side and had been singled out by Franco for reprisals. Large numbers of Basque were executed or imprisoned, and poverty and unemployment remained endemic until the 1950’s. In Fr. José’s words, “We lost the Civil War, and we became an occupied region.” However, the independent spirit of the Basques proved to be fertile ground for the ideas of Fr. José. He took on the project of alleviating the poverty of the region. For him, the solution lay in the pages of Rerum Novarum, Quadragesimo Anno, and the thinkers who had pondered the principles these encyclicals contained. Property, and its proper use, was central to his thought, as it was to Pope Leo and to Belloc and Chesterton.

“Property,” Fr. José wrote, “is valued in so far as it serves as an efficient resource for building responsibility and efficiency in any vision of community life in a decentralized form.” José’s first step was the education of the people into the Distributist ideal. He became the counselor for the Church’s lay social and cultural arm, known as “Catholic Action,” and formed the Hezibide Elkartea, The League for Education and Culture, which established a training school for apprentices. He helped a group of these students become engineers, and later encouraged them to form a company of their own on cooperative lines. In 1955, when a nearby stove factory went bankrupt, the students raised $360,000 from the community to buy it. This first of the co-operatives was named Ulgor, which was an acronym from the names of the founders.

From such humble beginnings, the cooperative movement has grown to an organization that employs over 100,000 people in Spain, has extensive international holdings, has, as of 2007, €33 billion in assets (approximately US$43 billion), and revenues of €17 billion. 80% of their Spanish workers are also owners, and the Cooperative is working to extend the cooperative ideal to their foreign subsidiaries. 53% of the profits are placed in employee-owner accounts. The cooperatives engage in manufacturing of consumer and capital goods, construction, engineering, finance, and retailing. But aside from being a vast business and industrial enterprise, the corporation is also a social enterprise. It operates social insurance programs, training institutes, research centres, its own school system, and a university, and it does it all without government support.

Mondragón has a unique form of industrial organization. Each worker is a member of two organizations, the General Assembly and the Social Council. The first is the supreme governing body of the corporation, while the second functions in a manner analogous to a labor union. The General Assembly represents the workers as owners, while the Social Council represents the owners as workers. Voting in the General Assembly is on the basis of “one worker, one vote,” and since the corporation operates entirely form internal funds, there are no outside shareholders to outvote the workers in their own cooperatives. Moreover, it is impossible for the managers to form a separate class which lords it over both shareholders and workers and appropriates to itself the rewards that belong to both; the salaries of the highest-paid employee is limited to 8 times that of the lowest paid.

Mondragón has a 50 year history of growth that no capitalist organization can match. They have survived and grown in good times and bad. Their success proves that the capitalist model of production, which involves a separation between capital and labor, is not the only model and certainly not the most successful model. The great irony is that Mondragón exemplifies the libertarian ideal in a way that no libertarian system ever does. While the Austrian libertarians can never point to a working model of their system, the Distributists can point to a system that embodies all the objectives of a libertarian economy, but only by abandoning the radical individualism of the Austrians in favor of the principles of solidarity and subsidiarity.

The Cooperative Economy of Emilia-Romagna. Another large-scale example of Distributism in action occurs in the Emilia-Romagna, the area around Bologna, which is one of 20 administrative districts in Italy. This region has a 100 year history of cooperativism, but the coops were suppressed in the 1930′s by the Fascists. After the war, with the region in ruins, the cooperative spirit was revived and has grown ever since, until now there are about 8,000 coops in the region of every conceivable size and variety. The majority are small and medium size enterprises, and they work in every area of the economy: manufacturing, agriculture, finance, retailing, and social services.

The “Emilian Model” is quite different from that used in Mondragón. While the MCC uses a hierarchical model that resembles a multi-divisional corporation (presuming the divisions of a corporation were free to leave at any time) the Emilian model is one of networking among a large variety of independent firms. These networks are quite flexible, and may change from job to job, combining a high degree of integration for specific orders with a high degree of independence. The cooperation among the firms is institutionalized many in two organizations, ERVET (The Emilia-Romagna Development Agency) and the CNA (The National Confederation of Artisans).

ERVET provides a series of “real” service centers (as opposed to the “government” service centers) to businesses which provide business plan analysis, marketing, technology transfer, and other services. The centers are organized around various industries; CITER, for example, serves the fashion and textile industries, QUASCO serves construction, CEMOTOR serves earth-moving equipment, etc. CNA serves the small artigiani, the artisanal firms with fewer than 18 employees, and where the owner works within the firm, and adds financing, payroll, and similar services to the mix.

The Emilian Model is based on the concept of reciprocity. Reciprocity revolves around the notion of bi-directional transfers; it is not so much a defined exchange relationship with a set price as it is an expectation that what one gets will be proportional to what one gives. The element of trust is very important, which lowers the transaction costs of contracts, lawyers, and the like, unlike modern corporations, where such expenses are a high proportion of the cost of doing business. But more than that, since reciprocity is the principle that normally obtains in healthy families and communities, the economic system reinforces both the family and civil society, rather than works against them.

Space does not permit me to explore the richness of the Emilian Model. I will simply note here some of its economic results. The cooperatives supply 35% of the GDP of the region, and wages are 50% higher than in the rest of Italy. The region’s productivity and standard of living are among the highest in Europe. The entrepreneurial spirit is high, with over 8% of the workforce either self-employed or owning their own business. There are 90,000 manufacturing enterprises in the region, certainly one of the densest concentrations per capita in the world. Some have called the Emilian Model “molecular capitalism”; but whatever you call it, it is certainly competitive, if not outright superior, to corporate capitalism.

Other Examples. There are many other functioning examples of Distributism in action: micro-banking, Employee stock option plans, mutual banks and insurance companies, buyers and producers cooperatives of every sort. This sample should be enough how distributism works in practice. Distributists are often accused of being “back to the land” romantics. The truth is otherwise. There are no functioning examples of a capitalism which operates anywhere near its own principles; there couldn’t be, because the mortality rates are simply too high. Hence, capitalism always relies on government power and money to rescue it from its own excesses. Distributism goes from success to success; capitalism goes from bailout to bailoutI visited Mondragon in the late 1980s in my capacity as Chairman of a trust which funded community enterprise in the West of Scotland and was deeply impressed - not least by the area's remoteness as I ascended a steep mountain in a hired car to reach the place. We need more celebratation of its achievements.

And the "way" which is shown in the picture is the new road which the village has built at the bottom of my garden. Not as fearsome as I had feared!!

Tuesday, October 18, 2011

Thinking

A cold but gloriously sunny morning here in Sofia (although eastern Bulgaria being lashed with rain and snow) – Vitosha’s 2 peaks capped in light snow making a marvellous backcloth for cycling on the cycle lanes, up Vitosha Boulevard to the old market area in the search for a tea set for entertaining. Then on to Sofia Art Gallery to buy the best book I know about Bulgarian painters in a European language (Die Bulgarischen Kuenstler und Muenchen - whose CD I had bought earlier but was not quite legible). Its focus is the influence of Munich’s Art Academy on Bulgarian painting in the century from the 1850s and it gives more then 40 painters a few pages each– many of them unknown to me. The route took us to the University area – so I decided to have another look at the Ilya Beshkov sketches I had been shown at a favourite gallery there – and bought three (including the one shown above which would have been very suitable for yesterday's post).

A friend recently asked for my recommendations for think-tanks which covered public management issues. My immediate thought was Demos and the Institute for Government which won last year’s UK Prospect Magazine’s Think Tank of the Year award) and which published in 2009 an important paper assessing how the British civil service compared globally. Despite this comparative element, however, most of their papers are, by definition, too tied to the current British (English) political agenda – which made me wonder about European Think Tanks.

The Wikipedia entry on the subject is actually quite useful – with good historical comment and a lot of links But a real find was a special website - On Think Tanks - which tries to pick up on ongoing themes. There are apparently now more than 6,000 such bodies in the world – a far cry from my early days when only the Rand Corporation and The Brookings Institute existed (we never thought of the Fabian Society in those terms). They seem to divide into four types –

• those which are strongly linked with academia and focus mainly on economic issues

• those which are explicitly sympathetic to a political party or set of political principles (the Fabian Society; the French political clubs)

• those funded (generally on a clandestine basis) by commercial interests to make the world a safer place for their pursuit of profits – particularly the extractive and drug industries. The campaigning journalist George Monbiot wrote recently about this. And the Mother Jones journal gave some useful examples of the link between funding sources and results. One website simply tracks the right-wing thinks tanks set up quite explicitly to protect the professedly "free market” agenda.

More entrepreneurial ones (a lot of which are found in central and east Europe) which offer bright ideas from a position of apparent independence

Of course, all Think Tanks profess their independence and rigour of methodologies but it is interesting that the European Commission is trying to insist that all Think Tanks register in the Commission’s Official Register of Lobbyists (albeit in a special section)

And, inevitably, we now have global league tables of Think Tanks – drawn up apparently with a highly arbitrary methodology

Diane Stone is a good analyst on the subject (not to be confused with Deborah Stone who wrote the best book on policy analysis – Policy Paradox!) who co-authored in 2004 what looks to be a great book on the global ThinkTank phenomenon Think Tank Traditions – policy research and the politics of ideas which has chapters on the various key countries. And you can read here a list of the German ones

Finally, a couple of speculative pieces on how Think Tanks need to smarten up their act – one which focuses on methodology; the other on technology

Monday, October 17, 2011

Identifying the real culprits

I haven’t said anything in the blog yet about the Occupy Wall St protest movement - which is most remiss of me. An article in what is a new magazine for me – Orion Magazine – expresses the issues very well

What is needed is a new paradigm of disrespect for the banker, the financier, the One Percenter, a new civic space in which he is openly reviled, in which spoiled eggs and rotten vegetables are tossed at his every turning. What is needed is a revival of the language of vigorous old (US) “progressivism”, wherein the parasite class was denounced as such. What is needed is a new Resistance. We face a system of social control “that offers nothing but mass consumption as a prospect for our youth,” that trumpets “contempt for the least powerful in society,” that offers only “outrageous competition of all against all.There’s also a good post (and discussion) on the Real Economics blogsite And Jonathan Scheel has an eloquent piece in The Nation on the subject.

And yesterday I came across the website of the marvellously-entitled Centre for the Study of Capital Dysfunctionality – set up before the global crisis at the London School of Economics by a financier who simply became disgusted with his experiences and now writes and talks eloquently about alternative systems.

He and others produced a book about the Future of Finance last year which (like a lot of others I suspect) I missed. It can be quickly downloaded hereand should be read in conjunction with the report which came from the Vickers banking commission which was set up by the UK Government in 2010

The Occupy Wall St movement is overdue (see my blog the Dog which didn’t bark) and is explained by two simple emotions – anger and impotence. Anger at the greed and wealth of a tiny group of financiers who provide no service but simply use invented money to sustain a sick way of life for themselves which impoverishes the majority. And impotence at a political system which not only gave them this opportunity in the first place – but shows no sign of wishing or being able to rein them in.

A recent, mainstream American book Winner Take All – how Washington made the rich richer and turned its back on the middle class explores these questions. How did the incredible inequalities arise? And why is the American political system acting so perversely – with voters apparently supporting the parties whose governments dismantled the regulatory systems and created the mess? The book shows quite clearly that American government is in bed with corporate power. No surprise there for many of us in Europe – but a bit of an eye opener for the average American reader whose access to such books is fairly limited. An excellent review (and discussion thread)summarises thus -

The book downplays the importance of electoral politics, without dismissing it, in favor of a focus on policy-setting, institutions, and organization. First and most important – policy-setting. Hacker and Pierson argue that too many books on US politics focus on the electoral circus. Instead, they should be focusing on the politics of policy-setting. Government is important, after all, because it makes policy decisions which affect people’s lives. While elections clearly play an important role in determining who can set policy, they are not the only moment of policy choice, nor necessarily the most important. The actual processes through which policy gets made are poorly understood by the public, in part because the media is not interested in them (in Hacker and Pierson’s words, “[f]or the media, governing often seems like something that happens in the off-season”).What is particularly interesting about the review is that it sets the book in the wider context of the malaise of American academic social science -

And to understand the actual processes of policy-making, we need to understand institutions. Institutions make it more or less easy to get policy through the system, by shaping veto points. If one wants to explain why inequality happens, one needs to look not only at the decisions which are made, but the decisions which are not made, because they are successfully opposed by parties or interest groups. Institutional rules provide actors with opportunities both to try and get policies that they want through the system and to stymie policies that they do not want to see enacted.

There is no field of American political economy. Economists have typically treated the economy as non-political. Political scientists have typically not concerned themselves with the American economy. There are recent efforts to change this, coming from economists like Paul Krugman and political scientists like Larry Bartels, but they are still in their infancy. We do not have the kinds of detailed and systematic accounts of the relationship between political institutions and economic order for the US that we have e.g. for most mainland European countries. We will need a decade or more of research to build the foundations of one.One of the discussants in the discussion thread on the book review asked what the European literature said on the matter. The only response was a reference to Wolfgang Streeck’s new book on Germany - Re-forming Capitalism; institutional change in the German political economy. Earlier this year I mentioned a couple of recent publications which have exposed the extent of big business influence on the EU – Bursting the Bubble (Alter EU 2010); and Backstage Europe; comitology, accountability and democracy by Gijs Jan Brandsma.

Hence, while Hacker and Pierson show that political science can get us a large part of the way, it cannot get us as far as they would like us to go, for the simple reason that political science is not well developed enough yet. We can identify the causal mechanisms intervening between some specific political decisions and non-decisions and observed outcomes in the economy. We cannot yet provide a really satisfactory account of how these particular mechanisms work across a wider variety of settings and hence produce the general forms of inequality that they point to. Nor do we yet have a really good account of the precise interactions between these mechanisms and other mechanisms.

The painting is (of course) by Georg Grosz - Eclipse of the sun - about the military-industry complex

Sunday, October 16, 2011

Can government ever change?

The UK Select Committee on Public Administration continues to do useful work – in identifying important questions to probe about the operation of government; and attracting witnesses from all sectors of society (including academia, Ministers and senior officials) to explore the issues with the Committee’s members. A few months it produced a report about government IT projects with the great subtitle - "recipe for rip-off". It is currently exploring the capacity of the civil service to deal with the Coalition government’s ambitious plans for "turning the model government upside down” – through contracting even more of public services to social enterprises. Its initial report Change in Government - the agenda for leadership came out last month and is tough not so much on the civil service as the government itself -

The Government has embarked on a course of reform which has fundamental implications for the future of the Civil Service, but the Government's approach lacks leadership. The Minister rejected the need for a central reform plan, preferring "doing stuff" instead. We have no faith in such an approach. All the evidence makes clear that a coordinated change programme, including what a clear set of objectives will look like, is necessary to achieve the Government's objectives for the Civil Service. The Government's change agenda will fail without such a plan. We recommend that, as part of the consultation exercise it has promised about the future role of Whitehall, the Government should produce a comprehensive change programme articulating clearly what it believes the Civil Service is for, how it must change and with a timetable of clear milestones.And this in one of the OECD’s “best governed countries” – according to a 2008 World Bank assessment. What chance, then, for the sort of cooperation between policy-makers, senior officials and academics in transition countries called for by the various analysts I quoted yesterday?

In short, the Government has not got a change programme: Ministers just want change to happen: but without a plan, change will be defeated by inertia.

The report goes on to set out what it would expect to find in a reform plan -

62. We consider that a number of key factors for success specifically relevant to large-scale Civil Service reform are vital to the success of change programmes in Whitehall:.Useful stuff!

a) Clear objectives: there must be a clear understanding of both what the Civil Service is being transformed from and to, as well as the nature of the change process itself. This requires both a coherent idea of the ultimate outcome, but also how clarity on how to ensure coordination of the reform programme and how to communicate that throughout the process.

b) Scope: The appropriate scope for the reforms must be established at the outset; with focused terms of reference, but also wide enough to be able to explore all necessary issues.

c) Senior buy-in: A political belief that reform is needed must be matched by the same belief within the Civil Service and ministers, and both should be clear on their roles in delivering it. Sustained political support and engagement from all ministers is crucial.

d) Central coordination: Either the Cabinet Office or reform units such as the Efficiency and Reform Group must drive the change programme. This requires good quality leadership of such units and a method of working which ensures collaboration with departments, and Prime Ministerial commitment.

e) Timescales: There must be a clear timetable with clear milestones to achieve optimal impact and to ensure political support is sustained. The lifespan of the change programme should include the time taken for reforms to become embedded. Two to three years is likely to be the most effective; beyond this period reform bodies may experience mission creep.

63. Measured against the factors for a successful change programme, the Government's approach to Civil Service reform currently falls short. There is no clear or coherent set of objectives, nor have Ministers shown a commitment to a dynamic strategic problem solving approach to change. The Cabinet Office have signalled their commitment to change the culture of Whitehall, but we have not yet found sufficient evidence to imply a coherent change programme. In the absence of leadership from the Cabinet Office, departments are carrying out their individual programmes with limited coordination and mixed levels of success. Without clear leadership or coordination from the centre, setting out, in practical terms, how the reform objectives are to be achieved, the Government's reforms will fail

We were snowed upon this morning in Sofia!

The painting is another Yuliana Sotirova which I have my eye on. Has a certain appropriateness for the theme of the post.....

Saturday, October 15, 2011

Can political and academic leopards change their spots?

Tempus fugit! It's time already to think about a paper for the 2012 NISPAcee Conference - which,again, will be held nearby - at Lake Ohrid in Macedonia.

The two previous papers I have presented at NISPAcee Conferences (in 2007 and 2010) were about the role of Technical Assistance in building the capacity of public bodies in transition countries. They basically argued that –

• Technical Assistance based on the logframe approach and competitive tendering is fatally flawed - assuming that a series of “products” procured by competitive company bidding for discrete projects can develop the sort of trust, networking and knowledge on which lasting change depends

• The EC's 2008 "Backbone Strategy" has not improved matters – the audit which led to the review was narrowly focused on procedural issues in the procurement process and the Backbone strategy continues with this bias.

• Few comparative and longitudinal studies have been carried out of administrative reform in transition countries – and in particular of the effectiveness of the various tools in the technical assistance cupboard of administrative reform. The myriad evaluations which the EC commissions of its institution building projects in the Region are formalistic and difficult to find – largely because of the commercial basis on which most technical assistance in this field is carried out.

• we are, to put it mildly, rather hypocritical in our expection that tools which we have not found easy to implement in our own countries will work in the more politicised contexts of East Europe and Central Asia.

At the 2012 Conference, I propose to elaborate the latter part of this critique; with respect to three issues -

a. Can the leopard change its spots?

One common thread in those few assessments which have faced honestly the crumbling of reform in the Region is the need to force the politicians to grow up and stop behaving like petulant and thieving magpies. Nick Manning and Sorin Ionitsa both emphasise the need for transparency and external pressures. Cardona and Tony Verheijen talk of the establishment of structures bringing politicians, officials, academics etc together to develop a consensus (see section 10.4 of this paper on my website). As Ionitsa put it succinctly –

The first openings must be made at the political level – the supply can be generated fairly rapidly, especially in ex-communist countries, with their well-educated manpower. But if the demand is lacking, then the supply will be irrelevant.This seems to imply an emphasis on civil society and democratisation – rather than institutional development.

b. Over-specialisation and lack of dialogueDepartmental silos are one of the recurring themes in the literature of public administration and reform – but it is often academia which lies behind this problem with its overspecialisation. For example, “Fragile states” and “Statebuilding” are two new subject specialisms which have grown up only in the last few years – and “capacity development” has now become a more high-profile activity. But the specialists in these fields rarely talk to one another – not least because of the professional advantages in pretending that theirs is a new field, with new insights and skills.

c. The superficiality of public managementInstitutions grow – and noone really understands that process. Administrative reform has little basis in scientific evidence (See the 99 contradictory proverbs underlying it which Hood and Jackson identified in their (out of print) 1999 book. The discipline of public administration from which it springs is promiscuous in its multi-disciplinary borrowing; new public management (still alive and well) is based on a mixture of dubious managerialism and theoretical eccentricities. Traditional PA was at least aware of politics and history. Technocratic NPM denies both.

My ambitious proposal for the 2012 NISPAcee Conference is to present a paper which will explore these issues through–

• A literature review of comparative assessments of administrative reform in the Region – and of the experience and lessons of the specific tools used

• A tentative exploration of the basis and contribution of the various “disciplines” to our understanding of institutional development

The painting is of St Joan Church on Lake Ohrid - by the esteemed Bulgarian Atanas Mihov (1879-1974)

Friday, October 14, 2011

Grim times for forgotten people

The house in the past week has been busy with guests – so not much chance to blog but lots of good conversation….wine and rakia. All of which needed in the colder and damp weather now being experienced here. So yesterday saw a trip to Teteven, nestling in the heart of the Balkan mountain range with the crucial aim of picking up local rakia from an old friend of Sylvie – my ex-landlady. After a speedy 80 kilometres on what must be the most scenic highway in the Balkans, a 3rd class road took us 18 kilometres through a lovely plain marked by signs of decline – but the industrial dereliction of Teteven still shocked us. The town straddles along a river and must have about a dozen derelict plants – of which the picture is typical. The only sign of economic activity is an Italian furniture factory. And a sad story of hopelessness emerged over the superb lunch which awaited us. Elections are in a few weeks – but the political class is seen as irrelevant and venal. I got the impression of a return to Hobbesian conditions – with youngsters having neither jobs nor hope; old people expected to live on a pension of 100 euros a month; and the European Union’s agricultural policy having shafted much of the rural self-sufficiency which produced such superb food in the past.

Friday, October 7, 2011

musical and visual tributes, visit to Dionysus shrine

First some musical tributes – sparked off by the very sad news that a guitarist legendary in my young days, Edinburgh-born Bert Jansch, has died - in his late 60s. I hadn’t realised he had an association with the Pentangle group which was a favourite of mine.

Billy Connolly, the great Scottish comedian, did a nice video on Jansch some years back.

Going down memory lane, I googled two other favourites of mine then - Pete Atkins (with words by the famous Clive James)and the Renaissance band

I visited Perperikon on Tuesday – an amazing medieval fortress topping a high hill with a superb 360 degree panorama (in the south to and beyond the Greek border). It was built in the place of an ancient Thracian sanctuary, related to the cult towards the Thracian equivalence of the Greek god of wine and feasts, Dionysius (known as Zagrey among the Thracians). It was discovered fairly recently; is still being excavated and is reckoned to have been built some 3,500 years ago - used for ritual sacrifices of animals and people. You have to be pretty fit to scramble up a steep trail for almost a kilometre – and then climb the stone staircases. I'm suffering today (knees)

Yesterday I had just over an hour’s drive to Blagoevgrad to visit a workshop on private-public partnership. Chatted with a couple of the participants and the trainer – then off to see the gallery of my favourite contemporary Bulgarian artist – Yuliana Sotirova. She is a very versatile painter – attracted to old buildings but good also with figures. She is also a sculptor (life size stuff). Before my visit, I had 6 of her paintings – including a magnificent oil one she did of my father from a black and white photograph which now hangs in my study in the mountain house. She must have more than 200 paintings in her studio – but after an hour she had 6 fewer.

This is one of a series of small paintings she has done of various church interiors - this one in Salonika. I will post others as space allows in the next few days.

The Guardian is the only UK newspaper I look at and was instrumental in Rupert Murdoch's recent humiliation. The Editor delivered recently a stirring (and rare) statement of the importance of a strong and free presswhich everyone should read.

And, if you are a cook and use garlic, this is a must-see video clip on how to peel a clove in 10 seconds flat without all the usual hassle (as a purist) I threw away my garlic crusher years ago

Wednesday, October 5, 2011

Rhodope charm again

I had hoped to be reporting on the great trip to Smolyian and Kardjali at the beginning of the week in the borderland with Greece – but was a bit knocked today by the cowboy behaviour of my Romanian village mayor. Perhaps its the just rewards for the positive Bulgarian postings I have been making! I was nicely received (as always) in the Smolyian Gallery on Monday - which has a very large space (3 floors) and a great collection but almost no money for maintenance. My colleague, Belin (who was leading the workshop) is an architect by training; now an academic; and was, in the late 1990s, a Deputy Minister for Regional development. He explained for me the ambitious agenda of the socialist government in the 1970s when they merged 3 villages there (as they did elsewhere) and created urban systems which are now tottering. He also suggested a possible reason for the very diffferent fates of villages in post-socialist Bulgaria and Romania. He suggests that land ownership was more completely collectivised in Bulgaria than in Romania – and that there was therefore no base left in Bulgarian villages post-1989 for the sort of self-sufficiency which still survives for example in my village amongst the old.

A marvellous journey on Tuesday through and over the mountains to Kardjali – quite amazing to see the isolated homesteads clinging so high up to the mountainsides! And all the minarets – most new. Kardjali has all the bustle and townscape of Turkish town. I was able, with some difficulty, to locate the art gallery – rather small and pathetic despite some great paintings - including the great Atanas Mihov (above)

and this delightful Stefan Ivanov.

RIP The Ceaucescu legacy lives on

Ceaucescu is alive and well and living on the Transylvanian border! I have just learned that at least a one metre footage of the land in front of our garden has been siezed by the municipality to build a 4 metres wide tarmac road to serve a one kilometre stretch with 7 houses – only 3 of which are permanently occupied and none of whose residents have a car or drive. The picture shows the stretch in question.

There has been no consultation. I was in the house for 7 weeks in the summer - left only on at the end of September and noone even mentioned it. The mayor phoned Daniela yesterday to ask her permission – assuring her that the fence would be restored – but the more we talked, the less attractive and sensible an option it seemed and an unhappy Mayor was duly told. But a telephone call to the old neighbour has just revealed that the work has in fact started. Amazing that a man in an official position can lie so brazenly - knowing that he will be found out! Such is the culture of arrogance which rules. Ironic that I am just finishing Tom Gallagher’s most recent book on Romania which reveals the succesful resistance the political elite fought against the basic EU requirement of Rule of Law. The illegal demolition of traditional old buildings by the Bucharest Mayor have been well documented by Sara in Romania and showed how the spirit of Ceaucescu was alive and well there. It seems he has now moved his attentions back to the rural areas.

There are several issues at stake -

1. illegal seizure of property

2. logic of the project; cui bono? Probably the hotel which is a carbuncle in the area and who encourage its younger guests to career around the tracks in the go-carts or whatever they are called

3. The lack of consultation

4. The poverty of imagination of politicians - who cannot see that they are destroying a priceless heritage. Poeple in the west would kill for the beauty and tranquillity of the village. Of course things cannot stand still; but there are better ways of attracting income than encouraging young vandals.

Watch this space.......

Monday, October 3, 2011

Rhodope charms

The Bulgarian roads are always a pleasure to drive – with the exception of some of the sinuous small roads which weave their way through the wooded hills which take up one third of the landmass of the country. I had a pleasant 4 hour drive yesterday afternoon - the first stretch along the superb and scenic open highway from Sofia to Plovdiv. Mountain ranges and valleys; then the lovely sight of the 2 pimple hills which stick out from the plain and mark ancient Phillipopolis; loop round the city and then under the stunning Assenovgrad fortress on another of these impossible rock-carved roads which characterise southern Bulgaria. As always a strong river also blasted its way through gorges and across the stones nearby. My exhaust suddenly developed a hole and I disturbed the sabbath as I spun through the tired but handsome old villages round the fashionable skiing resorts to reach Smolyian at 16.30. I was keen to visit their municipal art gallery again – last visited 2 years ago to my very great pleasure. Amongst other local artists, I was introduced to the work of Anastas Staikov by a Slovak woman who guided us around and introduced us to the Director. What struck me was what they were achieving against the odds – they had insufficient money to maintain their stock properly – let alone advertise it. I had assumed that the gallery would be closed Monday. It was very easy to find – as always it was the Regional history Museum which was signposted and I had a vague recollection that the art gallery was next door. And so it was. But Sunday is, unusually, closing day for it (although the history museum was open). The curator there took me next door where the Gallery Director was working and confirmed that it would be open tomorrow.

I have to confess at this stage that I have been accompanied on the travels since early August by a stray kitten whose cries were heard just as we were about to leave Sofia in the first week of August. Impossible to resist his charms, he travelled with great serenity and aplomb first the 375 kilometres to Bucharest – and, the following day, the 3 hour journey to the mountains. The mountain house was his heaven – 3 mice caught, for example. Since then, he has done another 1,250 kilometres – and could now reasonably considered un nomad veritable. I smuggled him into the Smolyian hotel in my rucksack – and, having slept for most of the 4 hours, he is now once more asleep at the back of the laptop. Hopefully he will not give the game away in the next 3 hotel overnights!

The painting is a Zdrawko Alexandrov from the Smolyian gallery

Sunday, October 2, 2011

In praise of self-sufficiency

For the last few years, it’s been fashionable for these with a concern about declining resources to measure their "ecological foorprint”. Although that seems a good rational device for relating our own actions to wider policy issues, it patently has had little effect on the way we live our lives. It may give us a measure of the social costs of the various decisions which make up our life style - but it gives little incentive to change. Orlov’s book gives a much more powerful measure – about the sustainability of the lives we lead – and speaks directly to our self-interest.

At the moment I live in two places - my mountain house in the Carpathians and the rented (garden) flat here in Sofia. So let’s apply the Orlov perspective to these two.

I bought the mountain house directly; have therefore no debt on it (or anything else) and my overheads are minimal. I installed a couple of years ago a wood-burning stove – but need some petrol and oil to drive the power saw to ensure continued supply (brought by horse and cart). So I should now buy a substantial stock of petrol and oil – with fire risks being reduced by storeage in the stone basement.

Water comes from the municipal system – so I need to install a proper rainwater catch - and get access to the neighbour’s natural (spring) system whose network he set up decades ago.

I need electricity only for music and internet (will it still exist?) since I have no television or frig – let alone washing machine! But I should consider a standby generator – driven by solar energy ( we have lots of sun). I have access to a vegetable garden on the neighbour’s land – and the rest of food can be obtained in the village most of whose households have livestock. There is no local sewage system – we all have our septic tanks – and I therefore try to minimise the water which goes down the drains. Basically the only thing the municipality supplies is garbage collection and water (which is why I pay only 50 euros a year local taxation – and about half that again for water)

As long as currency is useful (and the banks can actually give me my money when I ask!), I can pay for food – otherwise I have few skills to barter except English. My (English) library would be worthless – although some of the foreign artefacts could be traded. Stocks of soap and detergent (spices and wines!) should be bought up!

Connections between the Carpathian house and Sofia are, at the moment, fairly easy – a 600 kilometre drive. With scarce petrol resources, the public transport option would be a bit of a nightmare. A 10 hour train journey to Bucharest – then a 5 hour train, bus and hitching schedule. But at least hitch-hiking is still a serious transport option in Romania. It has disappeared in most European countries – even in Bulgaria. Here let me indulge an aside about a favourite topic of mine - the differences between Bulgaria and Romania. The Romanians have gone for American-style strip development of flashy new houses – which you rarely see in Bulgaria. But hundreds of Bulgarian villages have been bled dry – and lie derelict. That’s why Brits, Dutch and Russians alike have been able to pick up rural houses for a song. In Romania the villages emptied only in the saxon villages of Transylvania when the remaining German stock was enticed away by Chancellor Kohl’s incentives in the early 1990s – and immediately invaded by gypsies. Elsewhere the villages have seen the city people build new holiday homes.

Anyway - revenons aux moutons (back to our muttons) as the French say! Here in Sofia, I walk, cycle and use public transport. As an ex-socialist country, the urban layout and transport system is more akin to Russia's and therefore highly resilient. I assume that the small neighbourhood subsistence shops will still be able to bring in the fruit and vegetables from surrounding villages. But I am dependent on electricity and water – and unfortunately we don’t have the Soviet District heating system – or rather it has been given over to privatised monopolisitic suppliers who are already showing all the arrogance that status brings and recklessly over-charging (30 euros last month for water when I wasn’t here). I am actually thinking of buying a flat here (for access to the pleasant urban networks and facilities Sofia offers) so do need to check out the sustainability of its water and electricity systems.

So what I might call the "Orlov check” is useful in identifying actions which I should be taking in my own interest. But it also suggests that countries like Bulgaria and Romania should be more positive in recognising the value of a lot of what they currently have – a lot of which has to do with the issue of self sufficiency. People have learned not to trust the state – indeed to make do without it. The "modernising” opinion-leaders are ashamed of this feature in their countries – "autarchy” is, after all, a bad word in the economic lexicon – which should make us appreciate its inherent value.

We could start with the municipalities – the Sofia mayor and one of Bucharest sector mayors have started with bicycle lanes and, in Bucharest, even free rental of bikes. And I quoted recently a British example of encouraging local food production and use

Saturday, October 1, 2011

Resilience - a more appropriate national index?

Three questions arise from reading Orlov’s Reinventing Collapse – to which two of my recent posts have given extensive coverage

• Do European countries face the same collapse which Dmitry Orlov anticipates for the US.

• If so, what sort of differences will be evident in how the various countries such as UK, Bulgaria, Denmark, Germany and Romania , for example, cope?

• And what does that mean for our activities – whether personal or political?

Of course, countries such as England, Greece and Ireland already face severe economic and social crises – but the official rhetoric in these countries is that these are simply tough adjustments due to the excesses of (variously) bankers or specific governments. And that the bitter medicine will soon have us back on our feet agin. Orlov’s argument is completely different – that we are witnessing a breakdown of the Anglo-Saxon liberal model of economic governance (he doesn’t use this phrase) which seems to have served many of us well over the past 90 years. And that many millions face a return to basic self-sufficient living as the goods and services; and social and physical infrastucture we have become dependent on waste away and collapse.

I don’t want to offend my American readers (of whom I seem to have many) – and I’m sure they wouldn’t be reading my stuff unless they accepted that many of their systems and ways of living are excessive and inefficient. All the data tells us that US citizens are at one end of the spectrum in their resource utilisation and dependency. And advertising - and the media system it supports – beams this hedonostic and sybaritic way of life into even bedouin tents and creates enormous ambitions, envy and disatisfaction everywhere on the globe. The basic message is that it disables us all. I am an excellent product of the system - highly educated and well-read (and written) but pathetic at practical skills. My immediate reaction when something needs to be cleaned, repaired or built is to send for a house-maid, plumber or builder (at least I cook and can saw and chop wood!). In Romania I feel ashamed and inadequate – since most people (with the dangerous exception of the educated younger generation) build everything for themselves. I’ve already mentioned that this doesn’t figure in national statistics – and Romania and Bulgaria would actually rate quite high in the league tables if they were contructed around this coping or resilience factor (see tomorrow).

I’ve noticed that resilience has become a fashionable word in the past 2 years. The first paper I noticed was a 2009 Think Tank one – which basically seemed a neo-liberal take on how communities could cope with emergencies. But emergencies, by definition, are one off and short-lived events – after which things are assumed to return to normal. And this view is also evident in another interesting paper from the New Economic Foundation which looked at how a different set of national accounts might be constructed – in which resilience was, again, a factor. Bulgaria was rated very low on this index – although my experience of the modest lives they lead – with rural connections and excellent soil - suggests they would actually have a very high coping level (unlike England). And clearly Denmark and Germany would also cope very well. Sadly, despite France having heroically resisted the Anglo-saxon model culturally and protected its rural way of life, its urban spread and inequalities will not serve it well under crisis.

The UK’s Institute of Development Studies has a very useful overview of the various resilience measures in use. Access to food is a basic consideration in all these discussions – and here is a useful discussion paper on that issue. On the other hand, here is a typically crap academic treatment of the issue I realsie that I am only scratching the surface so far - and hope to return to the issue soon.

Friday, September 30, 2011

Vernissaj and wine

The Astry and Konus Galleries are both favourite ports of call for me here in Sofia. Vihra and Yassen are, respectively, highly sociable and knowledgable about Bulgarian painting - and helpful to outsiders like myself. Vihra - at Astry Gallery - organises special exhibitions every 2 months or so - with Vernissajs and bookmarks - and last evening was the first I have been able to manage. For a modest and talented young landscape artist - Sabit Mesrur - one of whose paintings heads this post.

Yassen - at the Konus Gallery - also teaches and I at last visited the small gallery which the Academy of Fine Arts has in Levski street, just round the corner from my flat. It has currently a nice little exhibition by one of the Academy's first graduates, Rumen Gasharov (1956). I was given a couple of excellent little booklets free of charge. I offered to make a contribution - but it was refused. His website should be here.

And today I opened another of the Magura range of wines I have mentioned before - from the very North-East of the country. This one of the "Rendez-Vous" label - Cuvee du Sud. Crisp and tasty. Highly recommended - if a bit pricey at 6 euros - from the great shop they have here in Sofia. It may be a bit far out - but a number 5 tram from Makedonia Bvd takes you down to Pushkin Boulevard very quickly and comfortably. They have great range of whites, reds and roses (including cheap but excellent boxes). Only pity is that they don't give wine-tasting......

Letter to the younger generation

At my stage of life, I sometimes get asked for career advice by some of the younger colleagues who have worked with me. I always find it difficult to know what to say since times and contexts (let alone individuals) are so different. And, as Oscar Wilde put it very aptly, "I always pass on good advice – it’s the only thing to do with it”! When I do try to answer – particularly in writing – I generally found that what came out was actually more helpful to me since I was forced to think about aspects of my life and its times to which I hadn’t given much attention. And I remember a couple of lovely books which were based on an older colleague writing to younger ones. The first "Lettres a une etudiante", was written by the French sociologist, Alain Touraine in 1974(and is sadly not available in English). I can’t at the moment remember the second author (it was probably C Wright Mills). But, in my Carpathian library, I have a marvellous book of reflective essays by the big names in European and American Political Science describing how they came to get involved in the discipline, who they worked with and were inspired by and how they came to write their various magni opi.