Politicians

are – and have long been – a good scapegoat for a society’s problems.

Spineless

and avaricious…So what’s new?

Well,

quite a lot actually. Fifty years ago, politics was important in Europe at any

rate – ideas and choices mattered.

It was actually almost an honourable

profession – people like Bernard Crick argued thus in 1962 in a classic and highly

eloquent “In Defence of Politics” which probably played some part in my own

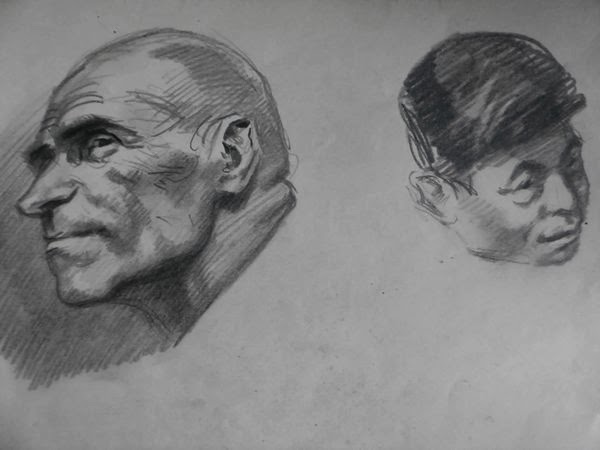

decision to go into (local, then regional) politics in 1968. (Daumier clearly had a different view of politicians in the early 19th century - which is why I've been using his caricatures to head this series of posts)

After

a couple of years of community initiatives and three years of chairing an innovative

social work committee, I found myself playing for 16 years a rather fascinating

but unusual role – nominally the Secretary of a ruling group of politicians

(responsible for some 100,000 local government professionals), I was actually

trying to create a system of countervailing power - of advisory groups of

councillors and junior officials challenging various conventional policy wisdoms;

and of community groups in the huge swathe of poor neighbourhoods of the West

of Scotland - trying to demonstrate

what “community enterprise” had to offer.

Political studies had been one of the key parts of my Master's Degree - so I was aware of the literature about democracy (such as it was then) - and, more particularly, elites (Mosca; Pareto; Schumpeter; Lipset; Dahrendorf; Michels - interestingly none of it british!).

But it was the experience of representing a low-income neighbourhood in a shipbuilding town which showed me the deficiencies of actual democracy and the reality of bureaucratic power. The local, working- class politicians who were my colleagues were pawns in the hands of the educated, middle class professionals who ran the local services. As a young middle class graduate, I saw an opportunity to challenge things - using my social science words and concepts - if not knowledge!

I had been inspired by the community activism of people like Saul Alinsky (and also by the early years of the American War on Poverty) and indeed wrote in 1978 two 5,000 word articles for Social Work Today (on multiple deprivation; and community development). The latter critiqued the operation of democracy and appeared in a major book on community development.

Straddling power systems was not easy (part of the important balancing process I have spoken about) – but, because I was seen as honest (if

eccentric), no one could unseat me from the post (for which I competed every two

years - from 1974-1990) as Secretary of the ruling Cabinet and Group of 78

Regional Councillors.

I

was also lucky also to have access in the 1980s to various European working groups –

and get a sense of how politicians and officials interacted there. And, most of

the time, still an academic. I was in the middle of a complex of diverse groups

– political, professional, local, national and European. It was the best education I ever had!

But

by the late 1980s I was beginning to see the writing on the wall – Thatcher was privatising

and contracting out local government functions – and abolishing any elected agency which tried

to stand up to her. Greed was beginning to be evident. Thereafter I have

watched events from a distance. I left British shores in late 1990 and became a bit of a political exile!

But most of it, I now realise,

was sheer verbiage and spin. Yesterday's post summarised the key points of the 1995 paper which superbly analysed the various phases political parties have gone through to reach their present impasse.

George Monbiot’s 2001 book “The Corporate

State – the corporate takeover of Britain” - exposing the extent of new Labour’s

involvement with big business - was my first real warning that things were

falling apart; that the neo—liberal agenda of market rather than state power was

in total control. And a wave of urbane, smooth-suited and well-connected young wannabe

technocrats powering through the selection procedures.

The

scale and nature of political spin – not least that surrounding the Iraq war - destroyed

government credibility like a slow poison.

The global debt crisis and bank bail-outs

shattered the myth of progress.

And then the media made sure to rub politicians’

noses in the petty excesses of expenditure claims.

Both political parties haemorraged

members – and then electoral support.

The

political party as we know it has exhausted its capital – but still controls

the rules of the game. They decide the laws; who is allowed to run; what

qualifies as a party – with how many nominees or voter threshold; with what

sort of budget; and with sort of (if any) television and radio coverage…

Parties

should be abolished – but it is almost impossible to do so because they will

always come back in a different form…….

I’m

just looking at a book which focuses on the fringes of the European party

system – the populist parties – and which does a good job of setting them in

the wider context.

We

have governments that no longer know how to govern; regulators who no longer

know how to regulate; leaders who no longer lead; and an international press in

thrall to all those hapless powers. Political parties no longer represent, banks

no longer lend……Current

political and social conditions are paradoxical: as citizens and individuals we

live lives that reflect the fact that we have more information and more access

to information than ever before – while at the same time we have a great deal

less certainty about our futures, both individual and collective. We are, some

would argue, increasingly living in conditions of ‘radical uncertainty’. …..

Uncertainty

returns and proliferates everywhere.’ As a result, one of the key variables

that needs to be factored into how

we understand both demands and mobilisation on the one hand and policies and

institutions on the other is anxiety.Not

the niggles and worries of everyday life, but rather the surfacing of deep

turmoil in the face of an uncertain future whose contours are barely

perceptible and thus increasingly frightening.

And,

though the condition of radical uncertainty might have existed, objectively, in

the past, it existed at times when there had been no experience or expectation

of the predictability of the future beyond that imagined in the context of

religious or magical beliefs. No experience of the desirability and possibility

of controlling our fate. Radical uncertainty in a world in which everyone has

come to prize autonomy and control is a different proposition all together

The

digital revolution provides an impetus for the transformation of populism from

a set of disparate movements with some shared themes and characteristics into

something that has the force of a political ideology. The accelerated quality

of political time and social media’s capacity to broadcast failure and dissent

mean that the digital revolution gives populist movements a steady supply of

political opportunity that reinforces its coherence. ...

And

in the face of the rather colossal set of forces and transformations that fuel populism’s

growth, curbing its destructive potential is about more than fiddling with an

electoral manifesto here and changing an electoral strategy there. Those things

need to be done, but they are minimum survival tactics rather solutions. The

problem is the manner in which populism as an ideology is capable of

marshalling the uncertainties and anxieties that characterise our era and

responding in ways that provide the illusion of reassurance. Illusory though it

may be, it fills that gap between the expectations of redemptive democracy on

the one hand and the lacklustre manoeuvring of panicked policy-makers on the other. A gap otherwise filled with

uncertainty and anxiety becomes filled

with populist reassurance.

Art

teacher (1928 - 1940) From 1940 lecturer , from 1957 to 1968 - professor of

painting at the Art Academy, Sofia , Dean of the Faculty of Fine Arts

(1957-1962) and Rector (1965- 1968. The Art School in Sofia bears his name.

Art

teacher (1928 - 1940) From 1940 lecturer , from 1957 to 1968 - professor of

painting at the Art Academy, Sofia , Dean of the Faculty of Fine Arts

(1957-1962) and Rector (1965- 1968. The Art School in Sofia bears his name.