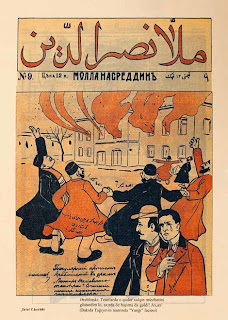

Yesterday’s post on the Azeri satirical journal of the 1920s

reflected my admiration of graphic arts as a whole - let alone those who do

caricature – which has been defined as “moral satire – making some point about

the nature of man rather than a specific individual”. I would amend that

slightly to replace “rather than” with “as much as” since some of the most

famous caricatures have savaged individuals. The classic caricaturists for me

are Goya and Daumier – with the Germans (Otto Dix, Georg Grosz, Kathe Kollwitz and Max Beckmann)

making a powerful contribution in the early part of the 20th century

before the later British caricaturists such as Gerald Scarfe.

A retired British politician who has such a great passion for political caricatures that he was instrumental in opening a London museum devoted to the art suggests on this interesting video on the history of British caricature that “graphic satire is an art form (the only one) which Britain created” – starting with William Hogarth. In his steps followed James Gillray (the work above is his - an ambassador presenting his "credentials" to the King - more here), George Cruikshank and Max Beerbohm

And delightful, comprehensive volumes have been published (in Bulgarian of course) on the first three of these individuals – Beshkov and Behar in the pre 1989 period; Angeloushev more recently.

Bulgaria at least honours its graphic artists properly.

Here's one blogger's introduction to eight old Bulgarian illustrators - a more general word, perhaps, than "caricature", "satire", "comic"........

A retired British politician who has such a great passion for political caricatures that he was instrumental in opening a London museum devoted to the art suggests on this interesting video on the history of British caricature that “graphic satire is an art form (the only one) which Britain created” – starting with William Hogarth. In his steps followed James Gillray (the work above is his - an ambassador presenting his "credentials" to the King - more here), George Cruikshank and Max Beerbohm

And, during my researches for this post, I was delighted to

find this glorious output from some Glasgow artists in the 1820s giving incredible insights into the lives of Glasgow people in those times.

I had been aware that it was not easy to find books (in

English) about this art form (however defined) or even its best practitioner

such as Daumier. A very useful 1980s article on the genre (the only one I could find on the internet) tells me that it has been viewed

down the ages as inferior. For the life of me I can’t understand why – since its

exaggerations and social scenes are far more inclusive and tell us so much more

than what passed for portrait painting.

A recent exhibition at New York’s Metropolitan Museum reminded us of the greats. For those who want to know more, here is a two hour video with three presenters. And there is a great website on Daumier which not only gives all his works but actually explains the background of each!

The Bulgarian tradition of caricaturists is a very strong

one – starting (I think) with Alexander Bozhinov a hundred years ago and

including people such as Ilyia Beshkov, Marco Behar, Boris Angeloushev and Jules Pascin whose main efforts were in the

pre-war period.

One of my prize possessions is a copy of a 1954 magazine called

New Bulgaria with each of its 18 pages covered with 3-4 amazing pencil

caricatures almost certainly doodled by Bulgaria’ most loved graphic artist –

Ilyia Beshkov.

One of my prize possessions is a copy of a 1954 magazine called

New Bulgaria with each of its 18 pages covered with 3-4 amazing pencil

caricatures almost certainly doodled by Bulgaria’ most loved graphic artist –

Ilyia Beshkov.

I was happy to pay 250 euros for the journal – after all I got 50 sketches for about the same price as the going rate for one (admittedly larger) caricature of his!

One of my prize possessions is a copy of a 1954 magazine called

New Bulgaria with each of its 18 pages covered with 3-4 amazing pencil

caricatures almost certainly doodled by Bulgaria’ most loved graphic artist –

Ilyia Beshkov.

One of my prize possessions is a copy of a 1954 magazine called

New Bulgaria with each of its 18 pages covered with 3-4 amazing pencil

caricatures almost certainly doodled by Bulgaria’ most loved graphic artist –

Ilyia Beshkov.I was happy to pay 250 euros for the journal – after all I got 50 sketches for about the same price as the going rate for one (admittedly larger) caricature of his!

And delightful, comprehensive volumes have been published (in Bulgarian of course) on the first three of these individuals – Beshkov and Behar in the pre 1989 period; Angeloushev more recently.

Bulgaria at least honours its graphic artists properly.

Here's one blogger's introduction to eight old Bulgarian illustrators - a more general word, perhaps, than "caricature", "satire", "comic"........

How artists coped during communist repression is a

fascinating subject - some (like Boris Denev and Nikolai Boiadjiev)

refused to toe the official line on painting and almost stopped painting; many

other moved into theatre design and cinema; others had to emigrate. One of

them, Rayko Aleksiev, so annoyed the communists that he was arrested on their

coming to power and died in prison under suspicious circumstances. An important

Gallery is named after him – on Rakorski St. Things eased only in the 1980s

largely due to the influence of PM Zhivkov's daughter who was a great art

afficiando!