George Monbiot’s post in yesterday’s Guardian gave me some

good links to papers trying to encourage a debate which is long overdue -

We think we know who the enemies are: banks, big business, lobbyists, the politicians who exist to appease them. But somehow the sector which stitches this system of hypercapitalism together gets overlooked. That seems strange when you consider how pervasive it is. It is everywhere, yet we see without seeing, without understanding the role that it plays in our lives. I am talking about the advertising industry. For obvious reasons, it is seldom confronted by either the newspapers or the broadcasters. The problem was laid out by Rory Sutherland when president of the Institute of Practitioners in Advertising. Marketing, he argued, is either ineffectual or it "raises enormous ethical questions every day". With admirable if disturbing candour he concluded that "I would rather be thought of as evil than useless." A new report by the Public Interest Research Centre and WWF opens up the discussion he appears to invite. Think of Me as Evil? asks the ethical questions that most of the media ignore – and adopts a rigorous approach, seeking out evidence. Our social identity is shaped, it argues, by values which psychologists label as either extrinsic or intrinsic. People with a strong set of intrinsic values place most weight on their relationships with family, friends and community. They have a sense of self-acceptance and a concern for other people and the environment. People with largely extrinsic values are driven by a desire for status, wealth and power over others. They tend to be image-conscious, to have a strong desire to conform to social norms and to possess less concern for other people or the planet. They are also more likely to suffer from anxiety and depression and to report low levels of satisfaction with their lives.

We are not born with our values: they are embedded and normalised by the messages we receive from our social environment. Most advertising appeals to and reinforces extrinsic values. It doesn't matter what the product is: by celebrating image, beauty, wealth, power and status, it helps create an environment that shifts our value system.

A pamphlet from the Compass Think Tank also picks up the issues. Less measured in its tone than the PIRC publication, it argues that advances in psychology. neurology and technology have given advertising insidious new powers; points to the interventions which governments have been making since the 1960s in relation to tobacco, protection of children etc and makes a series of recommendations – including the banning of advertising in public spaces, a measure introduced recently with great success apparently in the mega-city of Sao Paulo (20 million population).

Advertising may, as Monbiot suggests, have succeeded in the past few years in keeping its head down but there was a time when it was under attack. In my youth, I remember the impact of Vance Packard’s The Hidden Persuaders (1956 or so) and, a few years later, Jk Galbraith’s powerful dissection (in his 1967 book

The New Industrial State) of the reality of the market and the way large companies shaped demand. Of course, the downfall of large companies a couple of decades later by the more flexible Apple and Microsoft companies was

widely used to discredit Galbraith’s thesis. A more measured assessment of his arguments about corporate power (and indeed contribution to economics) appeared in

the Australian Review which said -

Two rejoinders are in order. First, the qualitative evolution of economic systems highlights that grand generalisations are necessarily period-specific. The character of the automobile market after the mid-1970s may be instructive, but it does not vitiate generalisations on its character before the mid-1970s.

Second, Galbraith’s generalisations regarding the unbridled power of the corporate sector retain direct relevance to other segments of the corporate sector—the military-industrial ‘complex’ (including constructors), big oil (centred on Exxon Mobil), the medical-insurance complex, big chemical, big tobacco, big retail (Wal-Mart) and big finance. It is curious that Galbraith’s critics have not sought to juxtapose Galbraith’s focus with current developments that involve corporate actors writing the legislation that governs their sector (medical-insurance), heading off legislation or penalties that adversely effect their sector (oil, chemical, tobacco, etc.), or channeling foreign policy with heinous implications (weapons contractors and constructors).

On the related issue of consumers as pawns, it is true that American consumers belatedly exercised autonomy in electing to buy the automobiles of foreign manufacturers (albeit a sub-sector of the market remains subservient to the US auto giants’ emphasis on sports utility vehicles and the preposterous Hummer). Galbraith rightly asked the rationale for the then vast sums spent by producers on marketing (a question never satisfactorily addressed by mainstream economists)

Most people, however, want to see the world’s economies refloated and jobs returning. Whatever their gripes about advertising, they see it as a means of aiding that objective. Those who see the huge waste and social destruction of our present system have an upward struggle. I was pleased to see people like Fritjof Capra and and

Hazel Henderson taking the argument into the enemy camp with a pamphlet published in 2009 by the Institute of Chartered Accountants of England and Wales – entitled

Qualitative Growth. I wouldn’t say it is the most convincing paper for such an audience – and am sorry that its references didn’t give wider sources

eg Douthwaite.

The problems of the economic system we have can be best be summed up in two words - dissatisfaction and waste. Advertising creates the first - and the economic machine wastes people, resources and the planet. And yet its ideologues have erected a propoganda machine which tells us that it is both efficient and effective! What incredible irony!

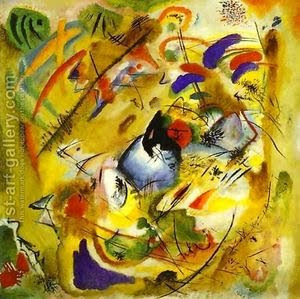

Last evening was spent very pleasantly at one of

Astry Gallery’s great vernissajs, celebrating the opening of yet another exhibition. This time the work of Natasha Atanassova and Nikolay Tiholov. Natasha is on the left and Vihra, the gallery impressario, on the right. And the painting at the top of the post is one of two I bought - this one by Natasha. The second is by Nikolay and is here -