I was once asked who I admired – and didn’t find it easy to answer. The dictionary definition (“to regard with wonder, pleasure or approval”)

doesn’t seem to me to go far enough. For me, to admire is “to look up to” and

has connotations not only of skill but of moral courage. I can admire someone’s

eloquence or writings – but not necessarily the person (not, at least in the

absence of knowing him/her). I can list some of my “heroes” – people who shone

a light at an important stage in my development – and whose work is still worth

reading. They would include George Orwell, Reinhardt Niebuhr, EH Carr, RH

Tawney, Karl Popper, Ivan Illich……and Tony Crosland who was the only one whom I

was fortunate enough to meet and talk with (briefly) when he visited my local

Labour Party when I was its chairman in the early 1960s - a few years after he

had written the definitive Future of Socialism.

When she heard that I was a politician from Strathclyde Region - with its mining traditions in Lanarkshire and Ayrshire - she presented me with a signed portfolio of her 1930s drawings of the NE English miners for onward donation to the Scottish miners.

And I almost forgot my memorable lunch with the Greek actress Melina Mercouri!

So what do all these stories tell? All but one of the people I;ve mentioned are dead! And those I met, I met only for a few minutes - 60 at most. Does this mean we can admire only from afar? Hopefully not.

In a future post I want to say something about "closer admiration"

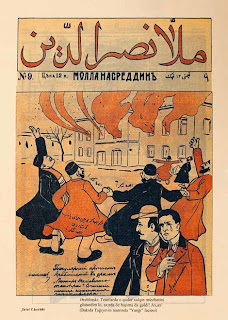

The painting at the top of this post is one of Tony Todorov - of whom I spoke yesterday

But it was his colleague Hugh Gaitskell whom I really admired for the courage he showed in the late 1950s – as Leader

of the Opposition – in standing up to fight for what he believed in. I had talked

with him at his house in the late 1950s (invited with other promising young

reformers) and was transfixed listening on the radio to his defiant speech at Labour's 1960 party conference where two unilateralist resolutions were carried and the official policy

document on defence was rejected. Gaitskell thought these were disastrous

decisions and made a passionate speech where he stressed that he would "fight

and fight and fight again to save the party we love". This was at a time

when I was highly ambivalent about the nuclear issue and would shortly

afterwards become an active nuclear disarmer. But I had to admire his courage

and oratory.

I was also lucky enough in those days to have a session

fixed up for me in the late 1960s with Wilfred Brown, head of the Glacier Metal company and the man who, with the help of Elliott Jaques, oversaw several experimental efforts in

empowerment, workplace democracy, compensation, pricing and organizational

design that culminated in the almost two-decade long efforts (1948-1965) led by

Dr. Elliot Jaques.

This unique collaboration between a CEO and a researcher — which Peter Drucker

called "the most extensive study of actual worker behavior in large-scale

industry" — resulted in one of the only true comprehensive systems of

management and led to groundbreaking discoveries and management methods that challenged almost every area of management and organizational design. For a simplified version of Brown's practice and theory see here.

Such a combination of leadership with respect for both

people and organisational learning is rare indeed

These memories of remarkable people I’ve met were sparked

off by an interview with Senator Bennie Saunders in the interesting Orion Magazine. He too I met (in the late 1980s) when he was

the “democratic socialist” mayor of Burlington, Vermont, USA. I happened to be

in Vermont, knew of him and asked to meet him (as a fellow democratic socialist

politician). He has shown immense guts not only in the various fights he has

taken on with corporate interests in his attempt to represent the ordinary

citizen – but for the simple act of not disguising his basic values.

Perhaps the most remarkable person I ever met was a Romanian

- Cornel Coposu – then (1991) Leader of the newly re-established Christian

Democratic Peasant Party who was

condemned in 1947 to spend 15 years in prison for his activities in the

National Peasant Party. After his release, Coposu started work as an unskilled

worker on various construction sites (given his status as a former prisoner, he

was denied employment in any other field), and was subject to surveillance

and regular interrogation.[]

His wife was also prosecuted in 1950 during a

rigged trial and died in 1965 soon after her release, from an illness

contracted in prison. Coposu managed to keep contact with PNŢ sympathisers, and

re-established the party as a clandestine group during the 1980s, while

imposing its affiliation to the Christian

Democrat International.

I also had brief but one-to-one meetings with two great German Presidents - Richard von Weizsacker and Johannes Rau. Weizsacker

was a Christian Democract and President 1984-1994 and West Berlin Mayor

1981-84. Rau was a Social Democrat; President 1999-2004 and Head of the

huge RheinWestphalen Land (Region) from 1978-98. I was lucky enough to

meet both of these men informally and can therefore vouch personally for the

humility they brought to their role. Weizsacker was holidying in Scotland and

popped in quietly to pay his respects to the leader of the Regional Council. As

the (elected) Secretary to the majority party, I had private access to the

Leader’s office and stumbled in on their meeting. Rau I also stumbled across

when in a Duisberg hotel on Council business. He was not then the President –

but I recognised him when he came in with his wife and a couple of assistants,

introduced myself ( as a fellow social democrat); gave him a gift book on my

Region which I happened to be carrying and was rewarded with a chat.

And then there was Tisa von der Schulenburg - Prussian aristocrat, nun and artist in 1920s Berlin who

supported her brother in the plot to assassinate Hitler whom I met a few years

before her death (at 97!) – at an exhibition of the sketches she had done in

the 1939s of the Durham miners.

Her experience of the darker moments of the 20th century was reflected in her sculpture and drawing, in which the subject of human suffering and hardship was a constant theme - whether in the form of Nazi terror or the back-breaking grind of manual labour at the coal face."Tisa" Schulenburg's life was by any standard remarkable. Having grown up among the Prussian nobility and witnessed the trauma of Germany's defeat in the Great War, she frequented the salons of Weimar Berlin, shocked her family by marrying a Jewish divorce in the 1930s, fled Nazi Germany for England, worked as an artist with the Durham coal miners, and spent her later years in a convent in the Ruhr.

When she heard that I was a politician from Strathclyde Region - with its mining traditions in Lanarkshire and Ayrshire - she presented me with a signed portfolio of her 1930s drawings of the NE English miners for onward donation to the Scottish miners.

And I almost forgot my memorable lunch with the Greek actress Melina Mercouri!

So what do all these stories tell? All but one of the people I;ve mentioned are dead! And those I met, I met only for a few minutes - 60 at most. Does this mean we can admire only from afar? Hopefully not.

In a future post I want to say something about "closer admiration"

The painting at the top of this post is one of Tony Todorov - of whom I spoke yesterday

.jpg)